Faster Horses

Creating a better problem

Faster horses

People claim that if Henry Ford built what people asked for, we wouldn’t have cars; we’d have faster horses. This statement is more myth than truth, but the idea holds water.

When I worked at GE, my users wanted “more storage” or “faster file transfer” when designing gas turbines. But these solutions were costly and didn’t solve the underlying problem: collaboration. My boss framed this as a collaboration problem to help me avoid a faster horses situation, which enabled me to implement lightweight virtual desktops and version control software—solutions that weren’t initially considered but solved the issue. Faster horses are everywhere, as we tend to over-index on the surface without going deep enough to understand the actual problem.

The danger of faster horses is the unforeseen outcomes they can create. For instance, saying “I want to lose weight” might be a faster horse—an uninspired, knee-jerk solution to a surface-level problem. The quick answer might cost an arm and a leg (literally) but then create other problems without solving the core need for better health.

Don’t let the current state taint an understanding of the problem.

Why? What If? How?

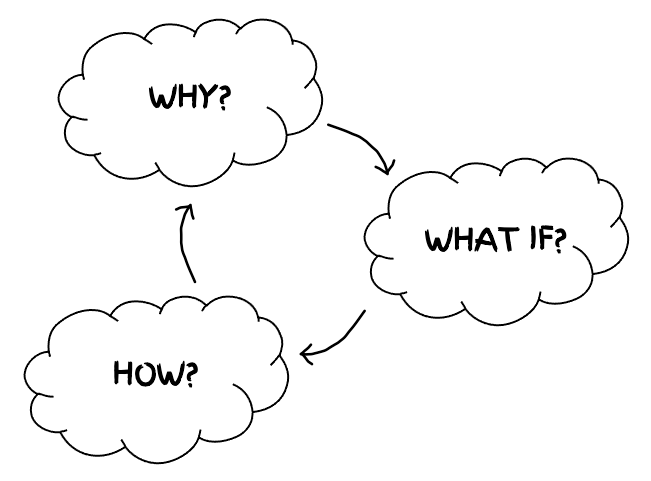

Creativity is seen as messy, chaotic, squishy, and overly associated with art, so its practical benefits are lost. But creativity can use a framework to make it less scary and undefined. Think of a three-question loop: Why? What If? How?

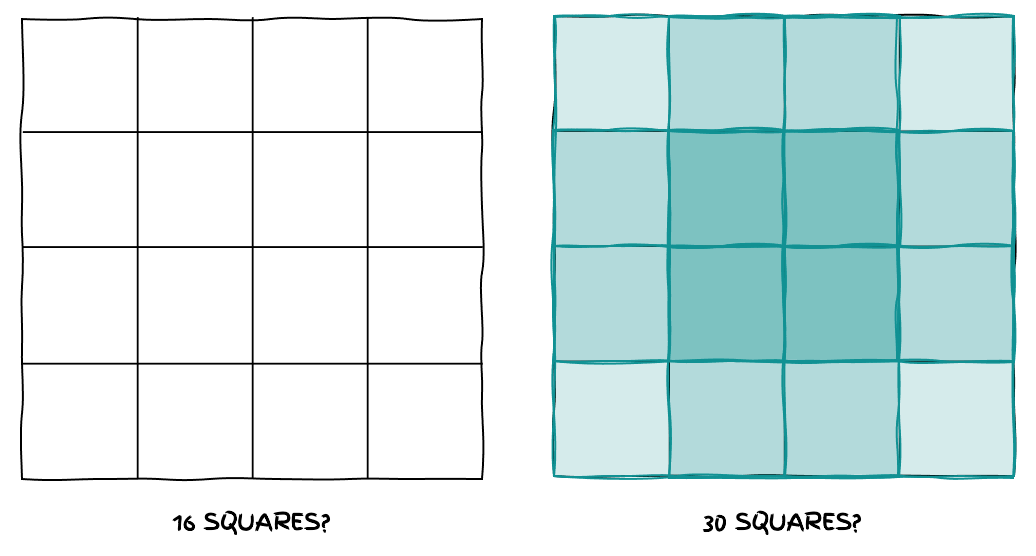

Why? seeks understanding, and it can be intentionally challenging. For instance, how many squares are below?

The “faster horses” answer is sixteen. But if we look closer, we’ll discover not only sixteen single squares but nine two-by-two squares, four three-by-three squares, and one four-by-four square. Asking why recursively forces perspective. Why do we want faster horses?

What If? helps us think of different combinations of existing things. For instance, Netflix combined video-rental with a monthly health club membership. For the faster horses problem, we could ask “what if trains could use roads instead of tracks?” Note the word “could.” Vocabulary is a minor detail, but it’s powerful. “Could” implies opportunity, choice, and abundance. “Should” implies a mandate, a decree, a fixed solution.

How? helps us stress-test solutions. We might find the What If proposal impossible. But we don’t have to get stuck here. We can start the loop of Why? What If? How? and loop and loop until we find something that works. This will take time, but it’s better to slowly solve the right problem than quickly invest in the wrong thing.

Mind mapping

Sometimes a visual artifact helps us understand a problem. A mind map is a tool I like for getting stuff out of my head. How to mind map:

1) Start with a central idea. Maybe it’s a theme, a single word, a problem, an image, an experience, a feeling.

2) Draw related ideas. Use Why? What If? How? as a starting point.

3) Draw secondary and tertiary ideas. Think of each sub-idea as the new center.

4) Connect ideas with lines. Do two unrelated things inspire a new concept to join them?

5) Embrace curves and color. Abandoning straight lines can relax your mind. Don’t be afraid to change an idea’s color or size.

6) Step back. You might have started with “faster horses,” but your exploration might have surfaced a new center—a more alluring idea.

Junk Drawer

Things I found interesting:

This directory of great articles when you need something to read

These AI-generated fake words

This search engine plants trees with the money made from your queries

P.S. Starting now, Turtle’s Pace is shifting to a bi-weekly cadence. That means you’ll hear from me every other Thursday. See you in February!

Excellent once again! Thank you for sharing 👍