Gravitational Pull

How we influence one another

Gravitational Pull

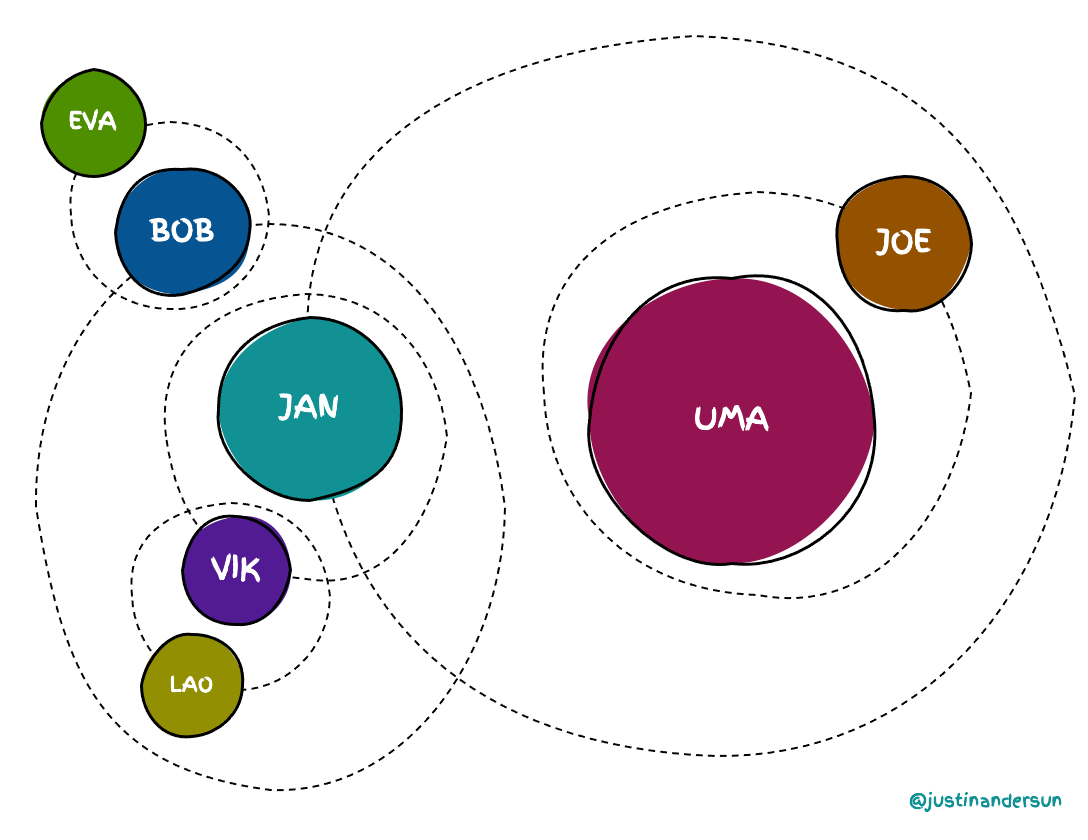

Imagine a group of people as a solar system. Be it a family, company, sports team, organization, church community, or a gaggle of friends—someone in the group is the sun, around which activities, decisions, and conversations orbit. A sun has gravity, and a sun-like person has the gravitas to pull others toward them.

In bigger groups, some people are planets—still orbiting the sun, but with a whole ecosystem of their own. Imagine a CEO as the sun of her company, and her direct reports are planets: Chief Technical Officer, Chief Marketing Officer, etc. Each officer has their own gravitational pull, around which their team, a cluster of moons, revolve.

Asteroids—visitors, consultants, etc.—might pass through the system and occasionally make an impact, but they don’t influence the group’s gravity.

When joining or interacting with a new group, I find it helpful to understand the gravitational pull. Who’s influencing whom? While titles in an organization might give some clues, they don’t reflect influence. Someone at the “bottom” of an org chart might have incredible sway over the system, like the Moon influencing Earth’s tides.

For instance: Uma is buried deep within Acme’s org chart. On paper, she has low decision power. The reality is that Uma has the most influence on product decisions, as she’s a founder with deep technical knowledge and innovative ideas. When wanting to expand the product offering, Uma influences Jan—the co-founding CEO—to bring them to market. Joe, another early employee, won’t follow orders unless Uma blesses them. Bob, Vik, Lao, and Eva were hired after Acme’s acquisition and are good subordinates who fall into their bosses’ orbits.

Knowing the gravitational pull of a group helps you understand how decisions are made. If you want things to change, influence the influencer.

Secondhand Smoke

I’m always amazed by how quickly a clever framing can sway public opinion. In the US, smoking went from a commonplace activity to a near-villainous crime within a half-century, almost entirely through advertising. Compared to other vices—alcohol, gambling, porn—smoking rarely resulted in violence, financial loss, or broken relationships. But, more than any other vice, smoking had a social cost.

Secondhand smoke influences others. It stinks up a room, pollutes the air for vulnerable populations, and lingers on clothes—signaling to others that you were around smoke and whether you were the one puffing the cigarette or not, that perception carries a social cost.

While fewer and fewer of us encounter literal secondhand smoke, we experience secondhand smoke of other varieties. The behaviors and opinions of those we surround ourselves with—at work, at home, and through the media we consume—influence us daily.

We might have a friend who steals cups from restaurants and makes us question our values. Or a parent who imbibes radical media, prompting us to radicalize in the other direction. Or an unaware coworker whose anxious tendencies create extra stress on our projects. Whether we like it or not, the people around us change us.

Jim Rohn famously said, “You are the average of your five closest friends,” which people use as an excuse to end friendships or cut “toxic” people from their lives. While there’s a time and place for this, there’s opportunity embedded in these challenging relationships. We can use them to strengthen skills we’d might not otherwise develop—like setting boundaries. As with designated smoking areas, we can create the right context with challenging people to minimize their influence on us. Smokers are more than their smoking.

While we can’t stop others from smoking, we have a say in how much their secondhand smoke will influence us.

The Slowest Hiker

I love the scenic beauty of Washington State—it’s the main reason I moved here. The problem is that everyone here loves the scenic beauty, so most hiking trails are crowded. When I hike, I constantly pass big groups because they can only move as fast as the slowest hiker.

Like the ancient adage, “A chain is only as good as the weakest link,” a group is only as fast as its slowest hiker. People can interpret this situation aggressively and resort to “cutting out the weak link” or only picking fast hikers. But that’s a crude solution and a pipedream to expect everyone to be above-average.

Instead, start with the slowest hiker. Move them to the front to set the pace. If you need to move quicker—look for ways to help the slowest hiker. Move some of their weight into the bags of faster hikers or give them extra water. By lightening their load and improving their experience, the whole group will move faster.

At work, distributing loads based on ability (rather than equality) make the team more productive and efficient. Beyond groups, this applies on a personal level. When setting expectations with yourself—i.e., how many words you can write in a day—plan with the slowest hiker in mind. On days when you’re stressed and tired, how many words can you complete? How can you make those “slow” days less slow? Can you pick up more on days when you’re feeling stronger? Being realistic about this enables sustained and steady progress.

You’re as fast as your slowest hiker.

Junk Drawer

A few nuggets of goodness:

Why it matters to make writing more readable

This quiz determines your creative personality (thanks, Mom!)

Another good post! It’s ironic that you mentioned comic sans, that was the font I used for my email at work for years.

This is awesome!👍