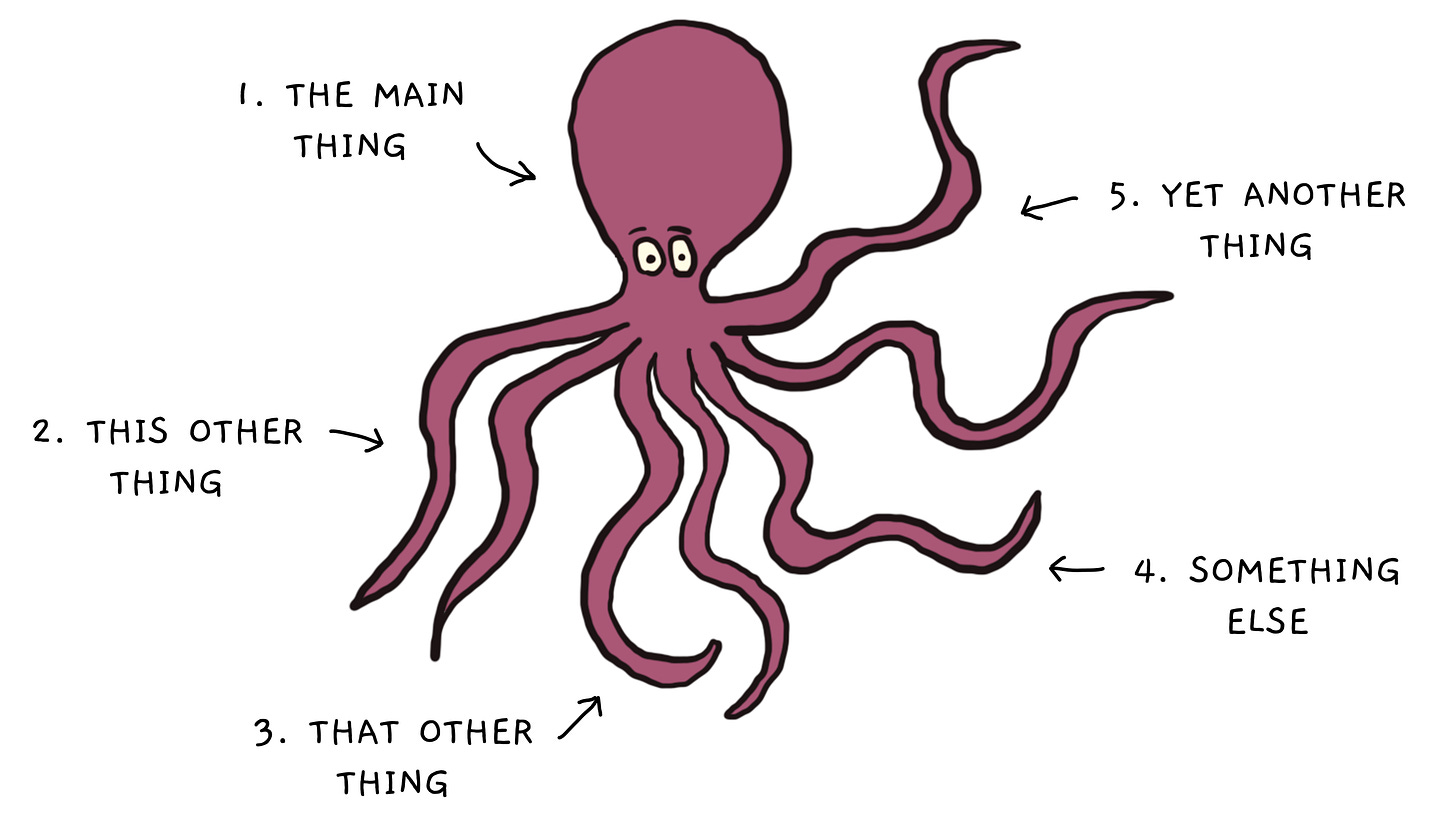

The Conversational Octopus

How to have a good conversation

The words we use to frame an interaction can flavor our behavior. For instance, are we having an argument or a conversation?

Argument is War

My recent fascination with the intersection of philosophy and linguistics has led me to Metaphors We Live By, which explores our relationship with metaphors and how they structure our social constructs. The book begins by dissecting an ancient metaphor: Argument is war.

When discussing arguments, we use terms like “gain ground” and “attack the opponent,” symbolic of military thinking. Since our language for arguments follows the patterns of war, we approach arguments similarly. This war-monger thinking may be productive for judicial cases, but it can make our colleagues feel threatened in situations of lesser stake. When we feel attacked, our blood level rises, and we get defensive.

Discussions with others don’t have to be combative; reframing an argument with a different term can change how we show up. For instance, a “conversation” might encourage collaboration.

But the connotations surrounding conversations may differ, as they might appear overly formal for some and too open-ended for others. So, I’d like to propose a new metaphor for conversation.

Conversation is an Octopus

The 2020 documentary My Octopus Teacher moved the masses to adore the eight-legged sea creature. An octopus is so different from us physically—looking like an alien creature and living in an exotic realm beneath the waves—yet, it shares many of our social traits: compassion for its fellow species, creativity, and gentleness. Octopi contain both these familiar and alien qualities, and this juxtaposition fuels our fascination.

Conversations share both these familiar qualities and alien qualities. For instance, we might converse with an old friend and recount memories of past years. We cover familiar topics, but our subtle differences in memory make the conversation feel alien, reminding us of our differences. Or maybe we’re speaking to someone for the first time. We may fumble at first in the alien ambiguity until we find familiar commonalities—reminding us that all people are similar.

But an octopus and a conversation contain more parallels than these shared qualities: They are structurally similar.

Some conversations begin with the central theme (the head) and explore differences and nuances, moving from the familiar to the alien.

Other conversations begin with a series of threads (the tentacles) before finding a uniting idea or shared connection, a move from the alien to the familiar.

Head-to-Tentacles

When conversations start with the head—such as project proposals or book clubs—we have a main thing and sub-topics to discuss. While these tentacle topics may be interesting or important, keeping the big picture in mind is essential. For instance, if we want to talk about the usability of a website (the head), we must be mindful of prolonged conversations about a UI library, branding decisions, or revenue targets (tentacles). These sub-topics might have relevance, but they aren’t the focus.

People’s natural curiosity and penchant for distraction make it easy for conversations to explode in multiple threads. Computing has a conversation-threading paradigm built into most messaging apps to solve this. Email programs like Outlook will clump messages into threads—each response a tentacle to the head message—or Slack will enable replies to specific head messages to avoid distracting the channel.

In formal settings, like legal casework, people leverage an argument map to systematically diagram the critical points in an argument and arrive at a conclusion. These can strangely resemble an octopus.

Off-screen, we can gently guide conversations from tentacles back to the head using a “parking lot.” A facilitator might use a whiteboard to “park” topics tangential to the main agenda. Even in less formal talks, we can steer a conversation back to its head by validating the tentacle, acknowledging its interesting aspects, and prompting a return to the central topic.

Tentacles-to-Head

Not all conversations should start with a defined head, and I’d argue that many vital discussions begin in the opposite direction: with the tentacles. These conversations can be hard to navigate if we don’t know where we’re heading, so they require more curiosity.

Unstructured conversations, like casual talks with family or meeting strangers, don’t have an agenda. They’re tentacle conversations. We try to find something in the murky water to grab, and some suction cups might not stick, so we may bounce to a few tentacles. After a while, we might discover a head we’re both interested in and unlock a deeper connection.

To find the head from a cluster of tentacles, use conversation threading:

Ask a question to get started. “Where are you from?”

As they respond, look for clues. “That’s why I enjoy traveling.”

Ask an open-ended follow-up question. “Where do you want to travel next?”

Share your thoughts. “Idaho is great; I climbed its highest point last summer.”

When a thread dies, experiment with a new one, starting at step one.

If both people are interested in conversing, one of the first three tentacles should stick, leading to a deeper connection.

Head or Tenacles?

By learning to discern a head or tentacle conversation, we can tailor our tactics:

Head-to-Tentacles: Stay on a topic using the parking lot or argument map

Tentacles-to-Head: Navigate to common ground via conversation threading

Junk Drawer

Use this tool to create fake people instead of paying for models.

Try these pattern palettes for your next design project.

Visually explore the bias of popular news sources.

This is another great blog! I love the octopus analogy , so accurate.👍