The Tragic Sandwich

A big decision requires many small decisions

A customer wanders into a deli to order a sandwich. He’s hungry after a long and stressful morning and wants something easy for lunch. Diabolical Deli was the best and nearest deli, and what could be more complicated than a sandwich?

The worker slips on plastic gloves and asks, “What kind of bread?”

Then:

“What size—six-inch or footlong?”

“How about protein?”

“What kind of cheese?”

“Toasted or untoasted?”

“Lettuce? Tomato? Peppers?”

“Any other toppings?”

“Avocado? It costs extra.”

“Which sauce?”

“How much? Light, medium, or heavy?”

Every decision is a collection of little choices—even for a trivial choice, like ordering a sandwich.

The Tyranny of Small Decisions

The tired customer isn’t thinking clearly, so he randomly responds to each question.

“Cinnamon bread.”

“Tuna.”

“Blue cheese.”

“Untoasted.” Why wait for the toaster oven?

“Jalapenos.”

“Heavy on the vinegar.”

The worker hands the sandwich to the customer. Relieved, the customer plops at a table and takes his first bite.

Nasty! How could he allow such a vile concoction of rubbish to slither down his gullet?

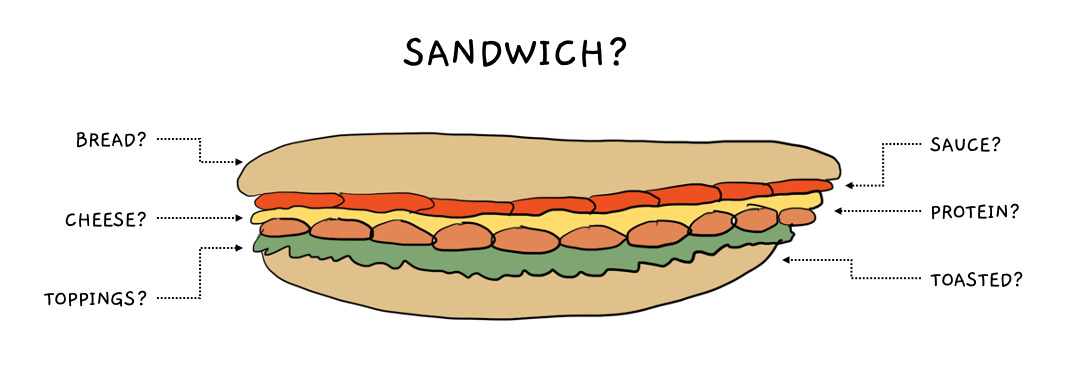

In isolation, each small decision was harmless and insignificant. Many baked goods come with cinnamon, and many great dishes feature jalapenos. But all these small decisions led to a bigger problem: An inedible sandwich.

Small choices flavor big decisions. One or two small mistakes may not impact the bigger picture, but several mistakes can tank an entire initiative.

Disgusted, the customer tosses the sadistically spawned sandwich in the trash.

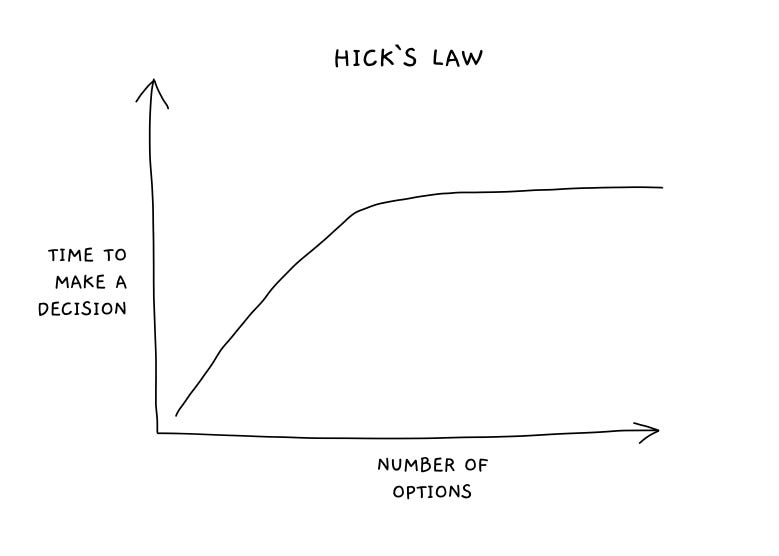

Hick’s Law

The customer returns to the counter to order a second sandwich. This time, he commits to carefully consider each option.

The deli worker restarts his litany of questions, and the customer reflects.

And reflects.

And reflects.

Plagued by analysis paralysis, he’s at a stand-still with the bread. He could choose whole wheat, asiago cheese, multigrain, white, sourdough, cinnamon, rye, or pumpernickel.

Hick’s Law states that increasing the number of choices will logarithmically increase the decision time. This means that a small list of options matters a lot while big lists don’t matter much—after a certain point, the decision time will be about the same.

When picking bread, a customer presented with six options will take about as long to decide as a customer with thirty options. For instance, Subway orders take longer than Jimmy Johns because customers have several options for each decision point. Jimmy Johns defaults to only one bread option, not requiring that choice for the customer. No wonder they’re Freaky Fast.

By the time the customer made his selections, it was dinnertime, and the worker had grown a long, unruly beard violating some health code. But the customer gets his sandwich and collapses at a table, almost too exhausted to eat it.

Many seemingly simple things are more complex once you peel back the bun. Consider all the logic behind a simple notification from Slack—a workplace chat system:

This one decision (to show a red dot or not) contains almost endless layers of complexity. The bigger the decision, the more small decisions are required to get the desired outcome. While it might seem annoyingly overengineered, that’s where all the richness lies. It’s one of the reasons why Slack is such a user-friendly employee collaboration software—their team respects the impact of small decisions. Inappropriate notifications—while trivial at face value—can be stress-inducing for individuals. With over 10 million daily active users, even a tiny change in notification logic can significantly impact workforce productivity and happiness.

The unique flavor, the remarkableness of a decision, comes from the little choices beneath the surface.

To avoid a tragic sandwich with important decisions—where to live, who to partner with, or how to pick a career—remember:

Small choices create big decisions.

Give yourself enough time to make effective decisions, even small ones.

Reduce the number of options to make a faster decision.

With a full belly and an empty mind, our customer leaves the Diabolical Deli with a newfound respect for small decisions. He’s happy he learned something, but after wasting so much time at a deli over a trivial decision, he is now concerned about his priorities. For tomorrow’s lunch, maybe he’ll order #12 at Jimmy Johns.

Junk Drawer

Ted Chiang (one of my favorite contemporary science-fiction writers) discusses how our obsession with finding intelligent aliens leaves us blind to the thousands of intelligent lifeforms going extinct around us in The Great Silence.

This graveyard of projects killed by Google is an excellent source of inspiration for your next side-project.

This newsletter by a fellow Substack writer features My First Million podcast write-ups. I learn a lot about entrepreneurship from the podcast and this newsletter offers good episode summaries.

This is so spot on! Thank you for sharing!👍😊