The Wrinkly Razor

The case for inconvenience in our smooth new world

At one AM on Easter Monday, I was somewhere in Wisconsin. Rain battered the windshield, and the wind threatened to shove me off the highway. Google Maps estimated three hours to get home. I had driven this route several times, yet here I was, looking at my phone to tell me to drive straight for 197 miles.

Suddenly, I heard Obi-Wan’s ghost in my ears: Use the Force, Justin.

Or maybe it was the caffeine speaking: Pay attention to the signs, Justin.

I flashed back to a solo road trip in 2012 when I left Ann Arbor to visit a friend in South Bend. No smartphone, no GPS, no MapQuest. Just me and the road.

Perhaps it was my 19-year-old self: Use your brain, Justin.

I closed Google Maps.

Our Smooth New World

It’s hard to remember life before the most basic apps like Google Maps. I remember going to garage sales with my mom, aunt, and cousins in my childhood summers. My mom would clip ads from the paper and drive to residences across Westside Grand Rapids. How she navigated to these addresses without GPS continues to baffle me.

Every time I press the button on my Keurig, let my face unlock my iPhone, or watch my Hue Lights fade to life at the sound of my voice, I remember I’m living in the future.

For me, the Apple Store was once a jarring, otherworldly place of glass walls, white tiles, smooth edges, and computers worthy of an art museum. Now, it feels like almost any other place. Its revolutionary design ethos has permeated most modern spaces, and its technology inspired entire industries of user-centric design, helping to shape the world into a miraculously convenient place. As evidenced by the COVID lockdowns, some of us can live in a perfectly seamless world: Join Teams meetings from a laptop in our bed, receive pre-made meals on our doorstep, walk on a treadmill in a climate-controlled room, and watch endless videos on our phones.

Modern life is like living on a conveyor belt; with little effort, technology carries us to our fates. And who are we to protest this smooth new world? No commuting is better for the planet, our wallet, and our schedule. Ordering items online is easier than making them ourselves and cheaper than buying them in brick-and-mortar stores. Not having to think about entertainment and getting curated content served the second we want it is irresistible.

Yet this smooth world sometimes feels like a life-sized game of Chutes & Ladders. As I run along, I am presented with options: A rickety ladder with splinted rungs dangling from the ceiling or a colorful chute at my feet. When I’m tired and stressed, it’s too easy to choose the chute and let it take me to another episode, processed snack, or digital rabbit hole. But sometimes, I can see the top of the ladder, where an aspiration balances on a shaky beam. I reach for the ladder, but the rungs evade me. I try to jump, but I can’t leave the floor. It’s like trying to move in a dream, but the floors are butter, and I make no traction. I fall down the chutes of distraction.

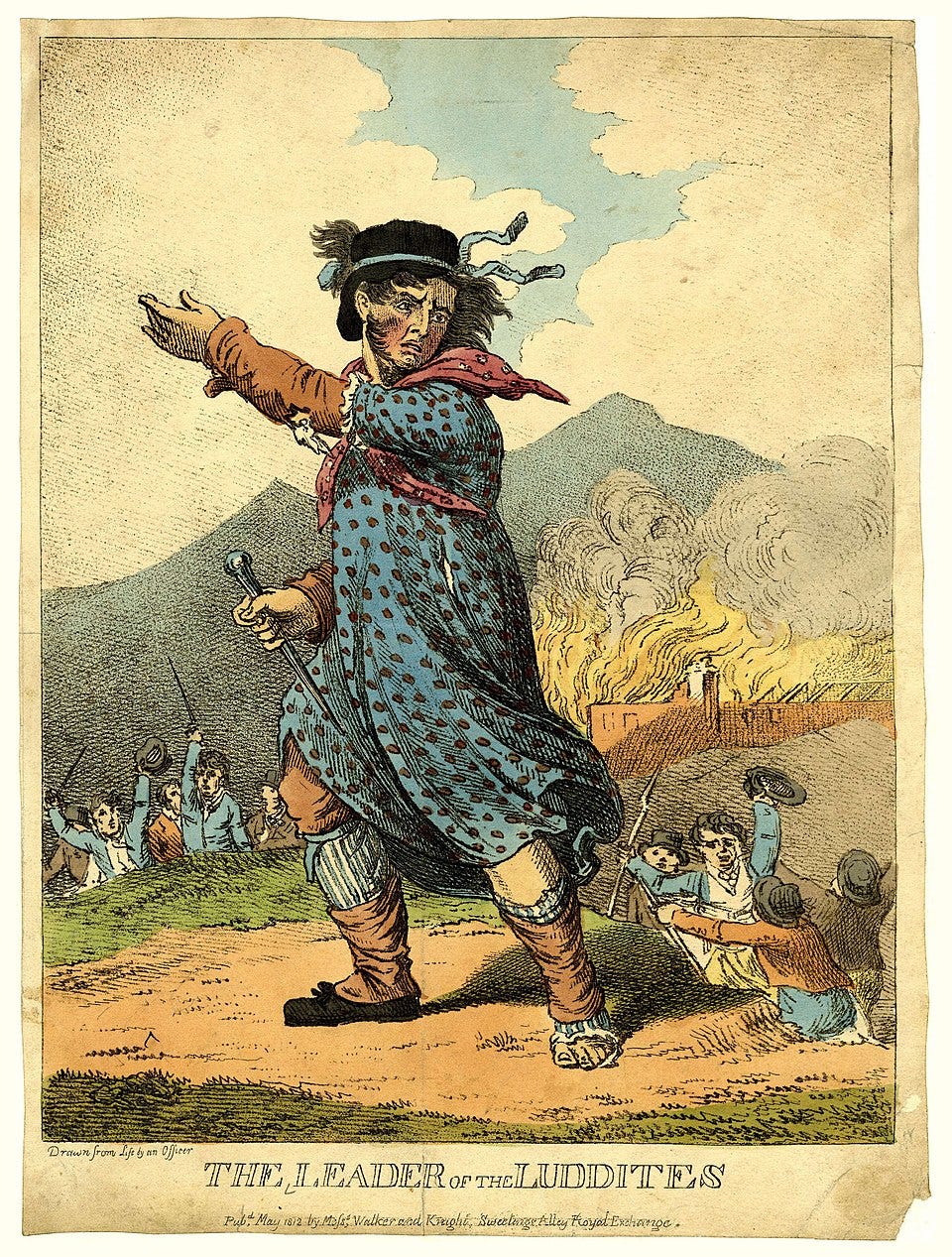

The Rise of Luddism

I cross the St. Croix River into Minnesota; so far, so good. Only forty-five minutes to go, but the tangle of the Twin Cities interstates lies ahead. Can I crawl across that web without Google?

It’s the middle of the night, and we have work in the morning. Getting home the most efficient way is the responsible thing to do. It will save precious time, money on fuel, and be safer in this sleep-deprived state. GPS is a great convenience, yet my phone stays dark.

Why do this irrational thing? Am I a Luddite?

Luddism is having a moment in the age of AI. A wide assortment of people I know hold strong opinions for resisting AI. When a fellow diver in my wife’s scuba-diving forum posted an AI-generated image of herself as an action figure, many criticized the environmental damage she caused by generating that image. Others argue a more humanist angle—that using AI is stealing good jobs from actual humans. Some succumb to reactionary politics and virtue-signaling. Another faction bemoans AI’s unforeseen consequences to justify their fear of change. Whatever the reason for this slow adoption curve, I find it interesting how we are quick to resist this tech while clinging so ardently to prior conveniences that have smoothed our brains.

I am no different. I would find it considerably easier to ask ChatGPT to write this essay, but here I am writing it long-hand. I’m not resisting AI because of the environmental impact or human rights reasons or some Ted Kaczynski-esque technophobia. I didn’t turn off navigation in Wisconsin to save data or protect my privacy from Google’s prying eye. While I’ve always been a bit of a masochist who purposely tries to make things harder for himself, that’s not why I avoid AI for writing or choose to drive without GPS.

The Wrinkly Razor

I read an article a few years ago about English cab drivers and how they needed to memorize the tangled streets of London to shuttle their passengers around the city effectively. A brain scan of these drivers revealed an enlarged hippocampus, as their brains physically adapted to store the complex spatial map they had learned. Their brains wrinkled to hold a map of the city. Ours risk staying smooth because we never even try to remember the way home.

A world in which we are not challenged to learn and adapt robs the brain of the opportunity to shape itself. While neuroscience has yet to fully study the effects of outsourced intelligence, I don’t think intellect is the proper measure. Life in a frictionless world is a spiritual problem.

The smooth world is a special type of hell. As we fall onto the conveyor belt of convenience and are carried through this stunning, curated space, we may wonder what lies above us. We may yearn to reach up and climb, but the ladders are precarious, and we feel we’ve lost our autonomy. Unable to live without tech, we begin to lose a spiritual war.

Sometimes, my urge to grab a ladder and climb is strong enough to force a leap. Many things I want to do, the things that feel the most rewarding and scratch a deep itch, like writing and mountaineering, require sustained effort and focus. To get words on a page or progress up a trail, you need traction. To get traction, you need texture.

You’ve likely heard the term “wrinkly brain” to describe an intelligent person with nuanced opinions. This term is a nod to the neurological idea that a brain with more folds and wrinkles has more neural pathways. I’ve come to think about technology from this lens, using what I call The Wrinkly Razor.

When evaluating a piece of tech, I ask:

“Does this wrinkle my brain?”

If the tech doesn’t allow my brain to form wrinkles, it’s probably worth shaving away.

Meetup is a useful tool because it enables me to find nearby people to engage with. It’s an app that drives more in-person interactions, making life more interesting. Hinge embraces a similar ethos in their marketing: “The dating app designed to be deleted.”

TikTok is a drug that numbs the mind with an endless stream of curated content. It’s a digital distraction that metaphorically (and perhaps physically) smooths the brain.

Most technology falls somewhere in the middle. Google Maps is essential when navigating a new place but can become a mental crutch in familiar locales. ChatGPT can be a fantastic utility for refining concepts and expanding ideas, but our creativity can atrophy if we forget how to write without it.

Reclaim Your Brain

At three-thirty AM, I realized I made a wrong turn. I’m heading north along the Mississippi River when I should’ve turned west onto I-394. This mistake cost me twenty minutes, time I could have easily saved had I been using GPS. But me and my principles, yet again, drove us off course.

But I’m not the only weirdo concerned with Wrinkliness. There’s a neo-Luddite subculture emerging in many parallel domains. Cal Newport, a computer science professor and public intellectual, speaks at length about the dangers of social media and has coined remedies that have permeated the cultural zeitgeist: deep work, digital minimalism, and slow productivity. Michael Easter, a fitness journalist, describes the comfort crisis that afflicts contemporary America and advocates for deliberately choosing discomfort in everyday actions, like taking the stairs instead of the escalator. Wendell Berry, Jenny Odell, and Matthew Crawford embody similar ethos in their writing. These thought leaders are collectively igniting a revolution against soul-sucking tech and conspicuous convenience.

I humbly suggest a critical nuance. Resisting the smooth world—our world of modernity, convenience, and smart devices—isn’t the goal. Nor am I suggesting we revolt against these forces and seek liberation from their suffocating regime. Why fight something when we could return to what’s natural?

The Wrinkly Razor isn’t rebellion. It’s a reclamation of effort, attention, and memory. Write the first draft by hand. Take the stairs. Handmake your pasta. Turn off the GPS. Let the wrinkles form as you find your way home.

Great read, when we travel there are times we use a map to plan our route if you know which direction the roads go you can make determinations to take alternate roads to get to your destination. If we get lost we'll use Google maps. Have a great day.

So agree with this. Although at my age part of the reason I don’t use tech as much as most is because of my lack of knowledge to operate it. I take the stairs at work and go to the library so I can read real books, and I refuse to always rely on GPS. Keep writing Justin!!