Beware Scale

The allure of the Ark in our Titanic times

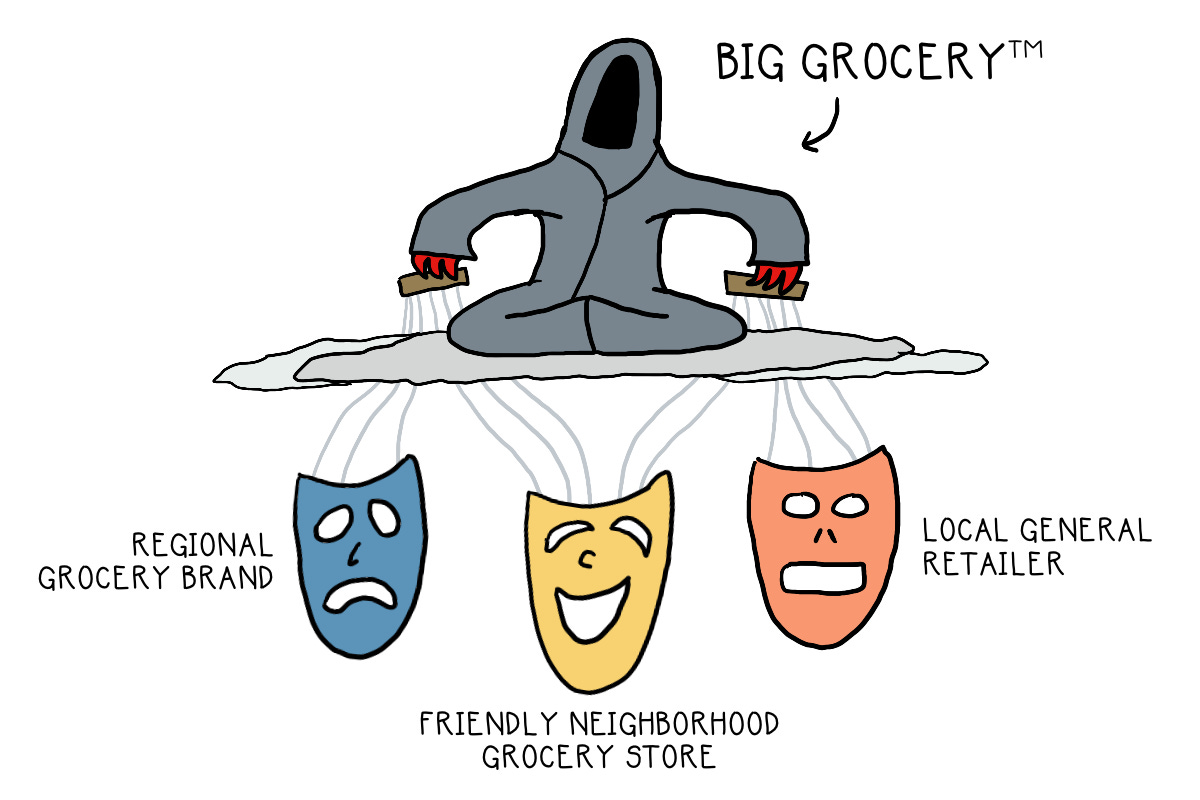

I live three blocks from three grocery stores with three unique names, yet they’re all owned by one company. QFC, Fred Meyer, Safeway—facades of the omniscient Kroger. All have the same generic brands and convenient discount programs, but consumers have the illusion of choice. I don’t necessarily have an issue with shopping at the grocery chain, but something about the masked monopoly gives me pause.

Perhaps this unease is spurred by my culture’s worshipping of small and local businesses. Ask anyone on the left or right, and they’ll agree that small, local businesses are preferable to big corporations. I agree with this at some level, but not that deep since I frequent a Kroger variant each week. But why do we believe that small and local is preferable to big and omniscient?

The Western zeitgeist features countless stories of the little guy overcoming a giant—from David & Goliath to Star Wars—and is perfectly embodied in this quote:

“The Ark was built by amateurs, and the Titanic was built by professionals.”

Perhaps our unease from shopping at large corporations stems from a spiritual sense that these large entities have lost touch with their essence.

Economies of scale

Any businessperson knows about economies of scale—doing things in bulk to yield larger profit margins.

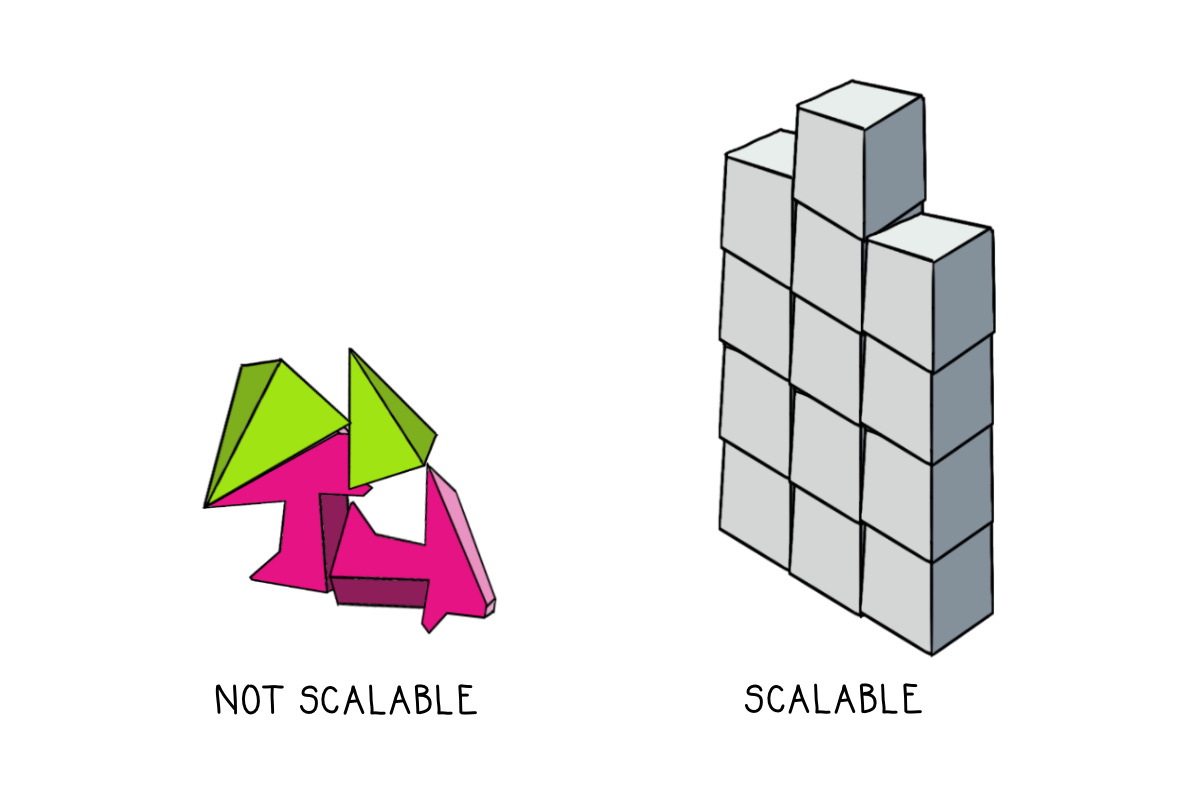

However, in the pursuit of scale, it can be easy to cut corners for efficiency—overlooking quality controls, safety measures, and working conditions. Each decision at scale amplifies the entity’s values. If they value exclusivity, many populations are marginalized. If they prioritize inoffensiveness, they might produce a bland experience for the masses.

It’s not hard to imagine a caricature of corporations—grey, soulless, yet miraculously dull and predatory at the same time—and perceive scale as a dog whistle for evilness.

Yet, scale is a requisite for growth—a value most of us share. Many entities, including some of those local businesses we hold dear, desire growth. They want to reach more customers, sell more products, and have more impact. But by pursuing scale, they can become victims of their success—generating pain for themselves and the people they serve.

Ten years ago, Amazon was a disruptive marketplace from which we could buy oddly specific car parts, out-of-print books, and equipment for niche hobbies—like unicycles. But as they scaled to offer more products and increase delivery speed, news of their working conditions made that shopping experience more guilt-inducing than exciting for consumers.

Perhaps this cycle is natural. A once beloved entity becomes too corporate, so we shift our affection to emerging small entities. Instead of buying books on Amazon, we feel a sense of righteousness by supporting small booksellers on Bookshop. But is the small entity, in its natural desire for growth, doomed to degrade its integrity in the pursuit of scale?

Modernity as a first principle

Before answering that question, let’s address a more fundamental assertion: growth is good.

Growth isn’t objectively positive. An overgrown lawn isn’t “good” from a realtor's perspective because it signifies an unkempt house and lowers sales potential. But growth to improve our quality of life—i.e., extending electricity and plumbing to anyone who wants it—is an aspect of modernity we accept as an immutable good. I’m not going to challenge that principle in this article, so let’s assume that extending modernity (i.e., clean water, Internet, access to unprocessed food, and suitable clothing) is an objective good.

From this premise, we can argue that pursuing scale is vital since it supports the growth of goods and services to a global population. We could not have developed and distributed a COVID vaccine without the scale of pharmaceutical companies and research institutions. In our inner-connected global society, scale enables us to maintain modernity. From this lens, we could appreciate Fortune 500 companies that fund retirement accounts and a national government whose tax dollars fund social programs. Yet, this worshipping of large entities feels icky.

Seeing the front

Even if scale is necessary for modernity, we should remain skeptical of it—both in the private and public sectors. At our jobs, we could keep our ears tuned for the harbingers of scale: Embrace change, achieve global parity, and become enterprise ready.

When an entity is scaling, much energy funnels into the positive marketing of growth: More opportunities, jobs, and profit. But there can be no light without shadow. A goal to achieve global parity could mean reduced focus on the existing regions where one does business. Increased spending on X program can mean divestment in Y program.

Awareness is one thing, but what can we do about this? Since scaling necessitates many people, the individual’s influence might seem limited. But this challenge is not new, and entities have navigated scale gracefully.

The military’s mental model of seeing the front reminds leaders to have regular experience in the trenches to see what’s happening on the frontline. They may notice depleted artillery resources or low morale. Seeing the front often and directly—not through a proxy or chain of command—can ensure they have an accurate lens of reality.

Toyota has introduced several mechanisms into its car manufacturing process that have evolved into industry best practices. Walking the Gemba is a practice for office employees to regularly wander the factory floor to stay connected with the core business. The Andon cord is a mechanism for factory workers to cease the manufacturing process upon finding a defect. Despite the cost of short-term efficiency, the Andon cord enables Toyota to stay diligent about quality at scale.

Organizations can stay rigorous with principles that enabled their early success—prioritizing the investigation of one-off problems, valuing anecdotes over aggregate data, or requiring all employees to manage customer support tickets. But what can an individual do?

Do things that don’t scale

The other week, I visited one of those nearby Kroger variants to purchase a greeting card. As usual, I felt the soulless aura as I browsed the mass-produced cards stuffed with corny messages. When I found a semi-decent one, I walked past the rows of unmanned cash registers to the self-checkout and grumpily rang up my order. As I walked out, the attendant smiled behind his mask and said, “Good to see you again – have a great day!”

This man had worked the self-checkout line—helping people with the kiosks—for over three years, and not once had I witnessed his spirit drop. Through the pandemic, the riots, and all the chaos that continued to pass through the store, he maintained an upbeat attitude and consistently expressed genuine kindness. As silly as it sounds, my negativity faded.

It’s easy to get down and complain about corporations and governments. But occasionally, we catch a glimmer of humanity within them—the people that choose to retain their spirit, not through rebellion but by merely doing their jobs.

There’s a famous, pithy quote tossed around by entrepreneurs: “Do things that don’t scale.” The self-checkout man at Kroger exemplifies this daily. He doesn’t get ground down in the gears of scale but stands out because of his humanity. And that, miraculously, spreads farther and wider than scale ever could.

Junk Drawer

Vote on the Internet’s top 50 productivity hacks.

Learn how a mega-flood created the Mediterranean Sea.

Follow this step-by-step guide to tech independence.

Another great one. I love the idea of non-scaling, very human activities within scaled-up organizations. I guess that's like, the Zappos customer service model, and maybe the philosophy that underlies a lot of large businesses that are surprisingly beloved, despite their scale.

Well written, and a bit scary.